Salmon and Trout Hatcheries

(Artificial Stocking)

Wouldn't life be easy if we could correct all the problems and damage done to our rivers by releasing artificially reared fish? There is seldom a more controversial topic in fishery management than that of artificial stocking but is this a solution for the Wye and Usk and what drives the polarisation of views?

Stocking can work: one only has to look at any of our reservoirs which can be made to hold considerable numbers of rainbow trout, stocked to order and secure in the confines of their environment, ready to deliver instant sport and bred large enough to evade most of the likely (but not all!) predators. But can it work for salmon, which have to travel 2,000 + miles to feed and then negotiate their way back to their natal rivers to spawn?

There are several techniques in the artificial stocking toolbox:

-

Translocation of adult fish above obstructions.

-

Egg boxes, planted directly into a tributary.

-

Hatcheries producing fry, parr and semi natural smolt release ponds.

-

Reconditioning kelts (spawned fish) to increase egg collection without depleting wild egg deposition.

Click here to read about the history of hatcheries in the Wye and Usk.

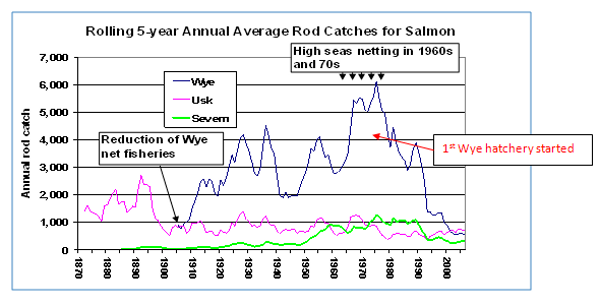

Our Policy

Declining numbers of rod caught fish are symptomatic of problems in the rivers and/or at sea. The Foundation's policy is to deploy methods that deal with the causes rather than the symptoms. An example of the effectiveness of such a policy is the Wye in Victorian times. By 1900 the river was so over-netted that the yearly rod catch had plummeted to below 450. However, it had a pristine and barrier free tributary system. The reduction in netting (cause) in 1901 resulted in a spectacular turn around in salmon numbers, as shown in the graph below.

This is an example where a hatchery would not have resolved the issue as the cause of the decline (extensive river netting) would not have been corrected.

Another example is the Tyne where the toxic state of the estuary prevented fish entering and leaving the river except in very high flows. In the mid-1960s when the water quality improved sufficiently to allow fish passage, the river became a salmon fishery again (it was a very good one before industrial pollution curtailed the runs, incidentally). The improvement was spectacular and helped further by the removal of the northeast drift nets 2003. Complicating the understanding of the issues behind the recovery, however, was a hatchery that was built to mitigate the effect of Kielder Water. This reservoir blocked off 7% of the catchment, which at the time already supported a good and improving population of salmon. The success of the Tyne recovery has often been incorrectly attributed to this hatchery. However, a long term assessment by the Environment Agency shows that it only accounts for 2% - 7% of the fish returning to the river. Please click here for the Tyne report.

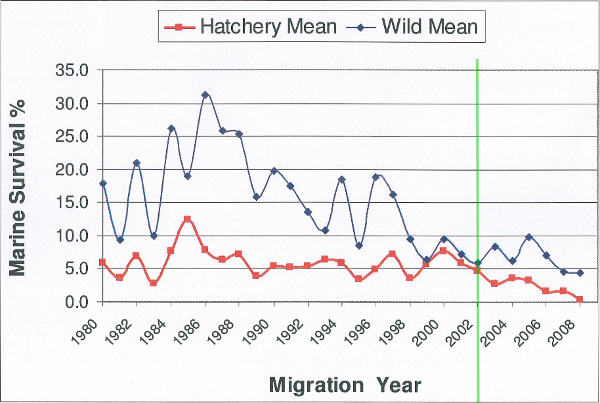

Today, both the Wye and Usk face a range of problems rather than a single issue. Not least is a seemingly inexorable decline in the % survival of smolts at sea as shown by the graph below. This long term sea survival decline has been met with reductions in the exploitation of salmon: the WUF buy-off of the estuary putchers and nets in 2000; the legal Irish drift net cessation in 2007 and the 2010 buy-off of the Lydney Park putchers and subsequent limit on their catches. Voluntary catch and release by the Wye rod fishery was superseded by a 100% release byelaw in 2012. On the Usk, catch & release is mandatory until 15th June and voluntary after that.

Marine survival (from smolt release to return to the coast) for wild and hatchery salmon in Ireland. In his book, "Swimming Against The Tide" (2010), Peter Gray, Keilder (Tyne) Hatchery Manager, omits the section post 2002 (or to the right of the green line) on this graph, yet includes the rod catch statistics from the Wye in 2010!

Our strategy therefore is to deliver permanent in-river works, including barrier removal, water quality improvements, habitat restoration and reduced estuarial salmon exploitation. This has several advantages:

- It is durable and sustainable. It benefits a wide range of species, including salmon, trout and other riverine species.

- It is substantially cheaper per fish than artificial stocking - particularly in respect of barrier removal and net buy-offs.

- It can be demonstrated to work.

- Funding can be obtained for these works.

- Risks to the whole stock are spread out, compared to the intermittent hatchery disasters i.e. not all "eggs are in one basket".

- It makes the best use of existing salmon stocks.

- Natural selection avoids complex genetic issues.

What we have noted as the arguments for artificial stocking for Wye and Usk:

- If there is sufficient adult stock along with uncommitted and unlimited funds, sites that are inaccessible to wild fish or where wild fish spawning is impossible could be stocked and overall salmon numbers thereby increased. This situation may not exist on the Wye.

- Mitigation is required resulting from permanent habitat loss from impoundments (reservoirs).

- Carefully selected and consistently good quality aquaculture can, in limited circumstances, achieve juvenile fish densities that are consistent with those achieved in the wild...but at a significantly greater cost than wild production

- It can make good 'population bottlenecks'. For example, shortage of spawning gravels, or egg mortality.

- Understanding the hatchery process requires no particular education, knowledge of fisheries, or concept of other issues - it a default assumption that there will be more fish in the river as a result.

- Stocking provides some with a "feel good factor".

And the arguments against stocking for Wye and Usk:

And the arguments against stocking for Wye and Usk:

- It is very expensive. Year on year costs need to be met and if the stocking process stops, the river reverts to its previous level without necessarily achieving any expansion of stock. The pre-existing problems remain.

- Stocking is limited by the areas suitable for planting out fish and availability of broodstock.

- Stocking is frequently at the expense of permanent improvements.

- The long-term assessment of results of historic stocking the Wye and Usk (NRA 1993) are very, very poor.

- When salmon stocks are below their conservation target and there are barriers that could be opened or water quality issues, there is evidence to show that artificial rearing is the worst option.

- Broodstock is taken at the expense of wild spawning and this reduction to wild spawning is never allowed for in any calculations.

- The survival rate post release of reared fish is substantially lower than that of wild fish.

- Hatcheries are prone to catastrophes, often resulting in an overall net loss to the river. These inevitable events seldom receive the full glare of publicity.

- There are dangers of mixing the genetics of fish whose unique survival mechanisms have evolved to succeed against challenging and changing river specific circumstances, providing a possible solution to impending problems such as climate change.

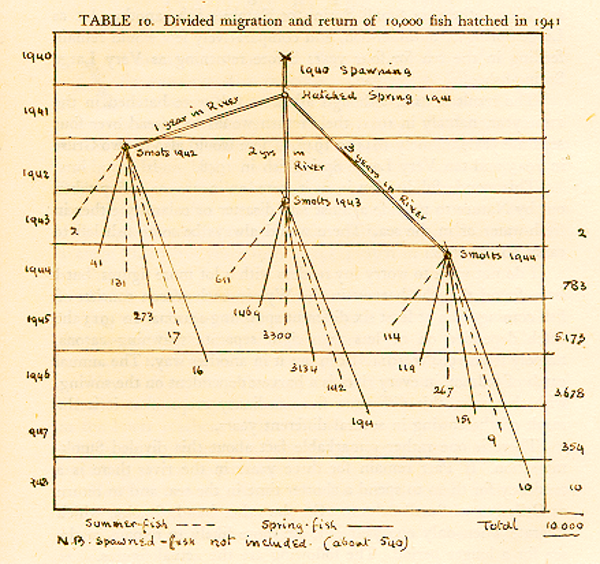

- The same applies to concerns over the loss of genetic integrity with respect to individual strains and different classes of fish. Please see the result of JR Hutton's long term scale reading survey.

DIVIDED MIGRATION. The table above, based on over 50,000 salmon scale samples, shows the sophisticated way salmon have evolved to survive catastrophic events. Wye salmon will be returning in each of seven years after one spawning year, and that is repeated in each subsequent year. This ability to adapt and compensate would be lost in artificially reared fish.

Additionally, there are a number of regulatory and legal considerations. The Wye and Usk site plans, drafted pre Natural Resources Wales (NRW) by the Countryside Council for Wales, regulator of both the Special Areas of Conservation (SACs), state that a hatchery should not be a method used in the management of the two rivers. The Agency has a set of practical constraints about sites that may be stocked and the numbers of fish that may be caught up. This is rigidly limited to 30 cocks and 30 hens on the Wye.

In conclusion:

The achievable levels of stocking will never restore the Wye, nor will a hatchery sort out the causes of the Wye's decline. We must therefore pursue other methods of restoration that are permanent and sustainable. The Usk also requires work to optimise salmon productivity and these other methods are the best use of available funds for both rivers.

The current situation:

Following a consultation Natural Resources Wales decided to close their operating hatcheries in Wales and to proscribe stocking salmon in all Welsh rivers. The consultation found no further evidence to support the use of hatcheries and so the last stocking has taken place using fish caught up in 2013. The money used to manage the Wye hatchery has been allocated for works on the river that go above and beyond existing and planned projects. The Cynrig site is now being used for educational and research purposes.

Against strong and, at times, over emotional opposition, NRW are to be congratulated for staying with the best available scientific evidence and pushing through the controversial but necessary measure.

Further reading:

Click here for the Wild Trout Trust's advice.

Dess hatchery 2011 survery bulletin

A Review of the Welsh Region Microtagging Programme 1984 - 1993 (G Jones)